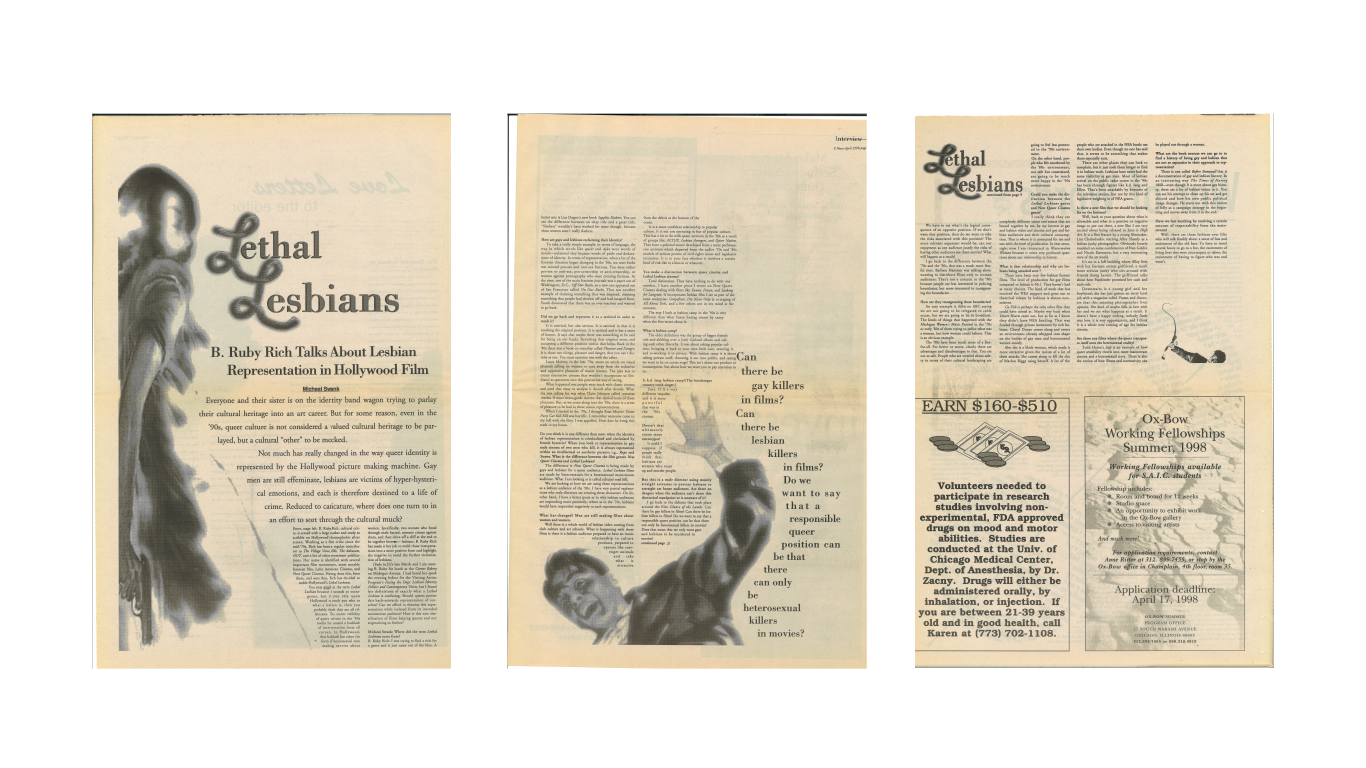

1998

Lethal Lesbians

Film critic B. Ruby Rich confronts Hollywood, and talks to F News about it.

Written by Michael Swank

Illustration by Shijing Li

Original Article

Everyone and their sister is on the identity band wagon trying to parlay their cultural heritage into an art career. But for some reason, even in the '90s, queer culture is not considered a valued cultural heritage to be parlayed, but a cultural "other" to be mocked.

Not much has really changed in the way queer identity is represented by the Hollywood picture making machine. Gay men are still effeminate, lesbians are victims of hyper-hysterical emotions, and each is therefore destined to a life of crime. Reduced to caricature, where does one turn to in an effort to sort through the cultural muck?

Enter, stage left. B. Ruby Rich, cultural critic, is armed with a large marker and ready to scribble on Hollywood's homophobic silver screen. Working as a film critic since the mid- 7Os, Rich has been a regular contributor to The Village Voice, Elle, The Advocate, OUT and a list of other prominent publications. Her name is identified with several important film movements, most notably feminist film, Latin American Cinema, and New Queer Cinema. Having done this, been there, and seen that, Rich has decided to tackle Hollywood's Lethal Lesbians.

You may giggle at the term Lethal Lesbian because it sounds so outrageous, but if you rely upon Hollywood to teach you who or what a lesbian is, then you probably think they are all villainesses. The recent visibility of queer culture in the '90s media has caused a backlash of interpretation from all corners. In Hollywood, that backlash has taken the form of heterosexual men making movies about women. Specifically, two women who bond through male hatred, commit crimes against them, and then drive off a cliff at the end to be together forever—lesbians. B. Ruby Rich has made it her job to mold those interpretations into a more positive form and highlight the negative to avoid the further victimization of lesbians.

[Fade in.] It's late March and I am meeting B. Ruby for lunch at the Corner Bakery on Michigan Avenue. I had heard her speak the evening before for the Visiting Artists Program's Facing the Dogs: Lesbian Identity Politics and Contemporary Voices, but I found her definitions of exactly what a lethal lesbian is confusing. Should queers protest this back-asswards representation of ourselves? Can we afford to theorize this representation while isolated from its intended mainstream audience? How is this new classification of films helping queers and not stigmatizing us further?

Micheal Swank: Where did the term Lethal Lesbians come from?

B. Ruby Rich: I was trying to find a title for a genre and it just came out of the blue. A better one is Lisa Dugen's new book Sapphic Slashers. You can see the difference between an okay title and a great title. "Slashers" wouldn't have worked for mine though, because these women aren t really slashers.

How are gays and lesbians reclaiming their identity?

To take a really simple example: in terms of language, the way in which words like queer and dyke were words of insult — reclaimed they became words of pride and declarations of identity. In terms of representation, when a lot of the feminist direction began changing in the '80, sex wars broke out around pro-sex and anti-sex factions. You were either pro-sex or anti-sex, pro-censorship or anti-censorship, or women against pornography who were creating factions. At the time, one of the main feminist journals was a paper out of Washington, D.C., Off Our Backs, so a new one appeared out of San Francisco called On Our Backs. That was another example of claiming something that was despised, claiming something that people had thrown off and had escaped from. Youth discovered that there was an over-reaction and wanted to go back.

Did we go back and represent it as a satirical in order to mock it?

It is satirical, but also serious. It is satirical in that it is mocking the original position. It is satirical and it has a sense of humor. It says that maybe there was something to be said for being on our backs. Revisiting that original arena and occupying a different position within that helps. Back in the '80s there was a book on sexuality called Pleasure and Danger. It is those two things, pleasure and danger, that you can't dismiss as one. You must examine one with the other.

Laura Mulvey, in the late '70s, wrote an article on visual pleasure calling on women to turn away from the seductive and oppressive pleasures of classic cinema. The idea was to create alternative cinema that wouldn't incorporate us (lesbians) as spectators into this patriarchal way of seeing.

What happened was people were stuck with classic cinema and used that essay to analyze it decade after decade. What she was calling for was what Claire Johnson called conscious cinema. A more avant-garde cinema that denied some of those pleasures. But, as we come along into the '90s, there is a sense of pleasure to be had in those classic representations.

When I started in the '70s, I thought Russ Meyers' Faster Pussy Cat Kill Kill was horrific. I remember someone came to my loft with the film. I was appalled. How dare he bring this trash to my house.

Do you think it is any different than now, when the identity of lesbian representation is criminalized and victimized by female hysteria? When you look at representation in gay male cinema of two men who kill, it is always represented within an intellectual or aesthetic pursuit; i.g., Rope and Swoon. What is the difference always represented within an intellectual or aesthetic pursuit; i.g, Rope and Swoon. What is the difference between the film genres New Queer Cinema and Lethal Lesbians?

The difference is New Queer Cinema is being made by gays and lesbians for a queer audience. Lethal Lesbian films are made by heterosexuals tor a heterosexual mainstream audience. What I am looking at is called cultural road kill.

We are looking at how we are using these representations as a lesbian audience of the '90s. I have very partial explanations why male directors are creating these characters. On the other hand, I have a better guess as to why lesbian audiences are responding more positively, where as in the '70s, lesbians would have responded negatively to such representations.

What has changed? Men are still making films about women and women.

Well there is a whole world of lesbian video coming from club culture and art schools. What is happening with these films is there is a lesbian audience prepared to have an ironic relationship to culture products, prepared to operate like scavenger animals and take what is attractive from the debris at the bottom of the ocean.

It is a more confident relationship to popular culture. It is not one operating in fear of popular culture. This has a lot to do with queer activism in the '90s as a result of groups like ACTUP, Lesbian Avengers, and Queer Nation. They have a political stance developed from a more performative activism which departed from the earlier '70s and '80s models of serious protest of civil rights issues and legislative initiatives. It is in your face whether it involves a certain kind of risk like at a kiss-in or whatever.

You make a distinction between queer cinema and Lethal Lesbian cinema?

Total distinction. They have nothing to do with one another. I have another piece I wrote on New Queer Cinema dealing with films like Swoon, Poison, and Looking for Langston. It incorporates lesbian film I see as part of the same enterprise; Grapefruit, Dry Kisses Only (a re-staging of All About Eve), and a few others not in mind at the moment.

The way I look at lesbian camp in the '90s is very different than what Susan Sontag meant by camp when she first wrote about it.

What is lesbian camp?

The older definition was the group of faggot friends ooh-and-ahhhing over a Judy Garland album and calling each other Dorothy. It was about taking popular culture, bringing it back to your own little cave, savoring it, and re-working it in privacy. With lesbian camp it is about taking private stuff, throwing it out into public, and saying we want to be on center stage! This isn't about our product or consumption, but about how we want you to pay attention to us.

Is k.d. lang lesbian camp? (The butchesque country torch singer.)

Sure. It is a very different impulse and it is more powerful that way in the '90s context.

Doesn't that ultimately create more stereotypes?

It could I suppose if people really think that lesbians are women who team up and murder people.

But this is a male director using mainly straight actresses to portray lesbians to straight art house audiences. Are there no dangers when the audience can't share this theoretical standpoint or is unaware of it?

I go back to the debates that took place around the film Silence of the Lambs. Can there be gay killers in films? Can there be lesbian killers in films? Do we want to say that a responsible queer position can be that there can only be heterosexual killers in movies? Does that mean that we only want gays and lesbians to be murdered in movies?

We have to say what's the logical consequence or an opposite position. If we don't want that position, then do we want to take the risks associated with this position? The more relevant argument would be, can our enjoyment as one audience justify the risks of having other audiences see these movies? What will happen as a result?

I go back to the difference between the '70s and the '90s, that was a much more fearful time. Barbara Hammer was talking about wanting to distribute films only to women audiences. That's not a concern in the '90s because people are less interested in policing boundaries, but more interested in transgressing the boundaries.

How are they transgressing these boundaries?

An easy example is Ellen on ABC saying we are not going to be relegated to cable access, but we are going to be in broadcast. The kinds of things that happened with the Michigan Women's Music Festival in the '70s or early '80s of them trying to police what was a woman, but how women could behave. That's an obvious example.

The '90s have been much more of a free-for-all. For better or worse. clearly there are advantages and disadvantages to that. You are not as safe. People who are worried about safety in terms of their cultural landscaping are going to feel less protected in the '90s environment.

On the other hand, people who felt smothered by the '80s environment, not safe but constrained, are going to be much more happy in the '90s environment.

Could you make the distinction between the Lethal Lesbians genre and new Queer Cinema genre?

I really think they are completely different issues and arenas that are bound together by me, by my interest in gay and lesbian video and cinema and gay and lesbian audiences and their cultural consumption. That is where it is connected for me and not with the level of production. In that sense, right now I am interested in Watermelon Woman because it raises very profound questions about our relationship to history.

What is that relationship and why are lesbians being attacked now?

There have been very few lesbian feature films. The level of production for gay films compared to lesbian is 40:1. They haven't had as many choices. The kind of work that has received the NEA support and gone out to theatrical release by lesbians is almost nonexistent.

Go Fish is perhaps the only other film they could have aimed at. Maybe way back when Desert Hearts came out, but as far as I know they didn't have NEA funding. That was funded through private investment by rich lesbians. Cheryl Dunye comes along and enters an environment already whipped into shape on the bodies of gay men and heterosexual women mostly.

Also she is a black woman, which made it more attractive given the racism of a lot of these attacks. She comes along to fill the slot of Marlon Riggs using herself. A lot of the people who are attacked in the NEA battle use their own bodies. Even though no one has said that, it seems to be something that makes them especially nuts.

There are other places they can look to complain, but it just took them longer to find it in lesbian work. Lesbians have never had the same visibility as gay men. Most of lesbian arrival on the public radar screen in the '90s has been through figures like k.d. lang and Ellen. That's been attackable by boycotts of the television station, but not by this kind of legislative weighing in of NEA grants.

Is there a new film that we should be looking for on the horizon?

Well, back to your question about what is allowable and what is a positive or negative image to put out there, a new film I am very exited about being released in June is High Art. It's a first feature by a young filmmaker, Lisa Cholodanko, starring Alley Sheedy as a lesbian junky photographer. Obviously loosely modeled on some combination of Nan Goldin and Nicole Eisenmen, but a very interesting view of the art world.

It's set in a loft building where Alley lives with her German actress girlfriend, a much more serious junky who sits around with friends doing heroin. The girlfriend talks about how Fassbinder promised her such and such role.

Downstairs is a young girl and her boyfriend; she has just gotten an entry level job with a magazine called Frame, and discovers that this amazing photographer lives upstairs. She kind of maybe falls in love with her and we se what happens as a result. It doesn't have a happy ending, nobody finds true love, it is very opportunistic, and I think it is a whole new coming of age for lesbian cinema.

Are there any films where the queer transposes itself onto the heterosexual reality?

Todd Haine's Safe is an example of how queer sensibility travels into more mainstream cinema and heterosexual story. There is also the notion of how illness and normativety can be played our through a woman.

What are the book sources we can go to to find a history of being gay and lesbian that are not so separatist in their approach to representation?

There is one called Before Stonewall that is a documentation of gay and lesbian history. In an interesting way The Times of Harvey Milk — even though it is more about gay history, there are a lot of lesbian voices in it. You can see his attempt to clean up his act and get elected and how his own public political image changes. He starts out with this notion of folly as a campaign strategy in the beginning and moves away from it in the end.

Have we lost anything by receiving a certain amount of respectability from the mainstream?

Well, there are those lesbians over fifty who will talk frankly about a sense of loss and excitement of the old bars. To have to travel several hours to go to a bar, the excitement of living lives that were circumspect or taboo, the excitement of having to figure who was and wasn't.