1995

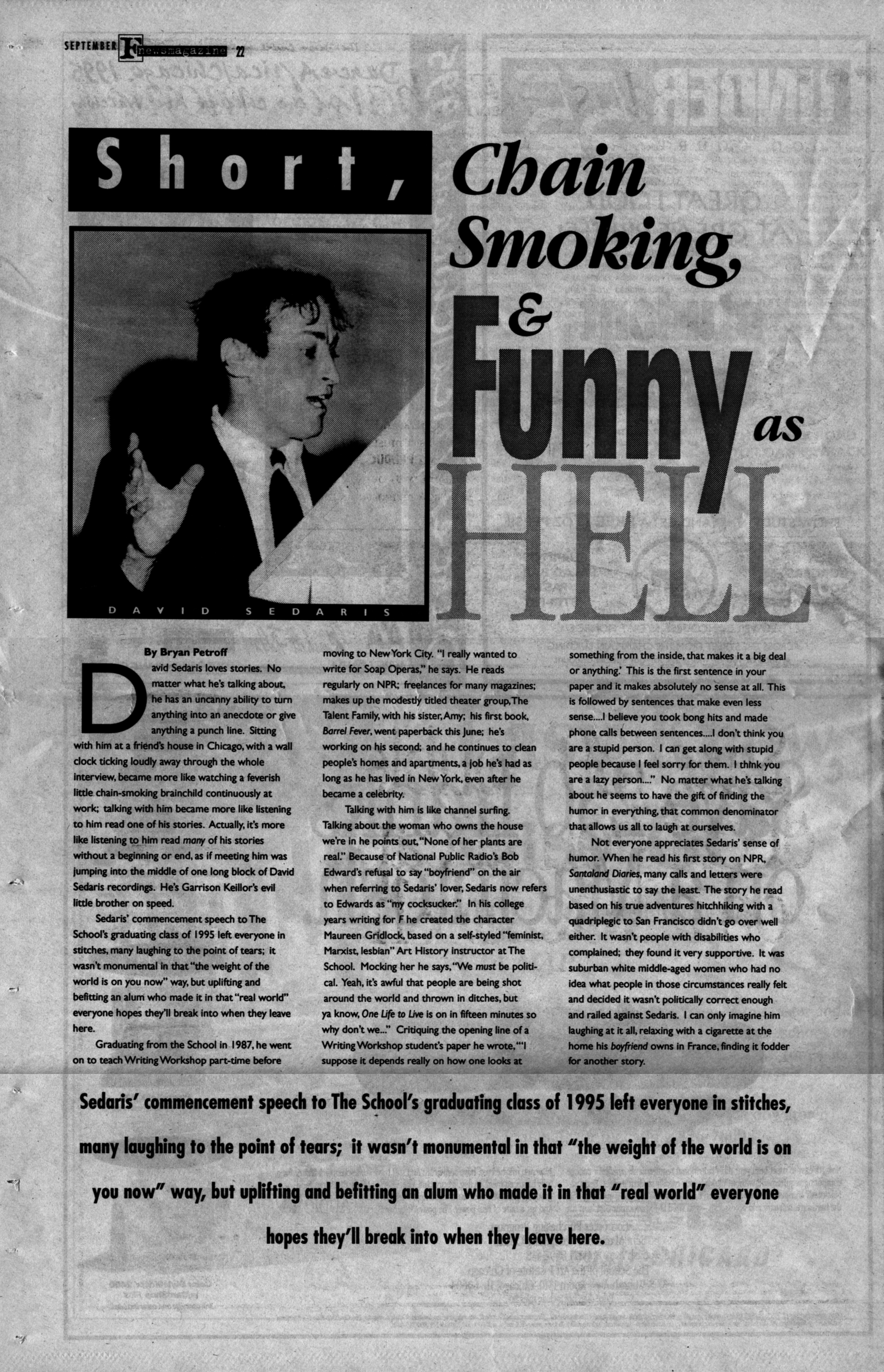

Short, Chain-Smoking,

& Funny as Hell

In which SAIC alumnus David Sedaris can't talk about his boyfriend on NPR.

Written by Bryan Petroff

Illustration by Shijing Li

Original Article

David Sedaris loves stories. No matter what he's talking about, he has an uncanny ability to turn anything into an anecdote or give anything a punchline. Sitting with him at a friend's house in Chicago, with a wall clock ticking loudly away through the whole interview, became more like watching a feverish little chain-smoking brainchild continuously at work; talking with him became more like listening to him read one of his stories. Actually, it's more like listening to him read many of his stories without a beginning or end, as if meeting him was jumping into the middle of one long block of David Sedaris recordings. He's Garrison Keillor's evil little brother on speed.

Sedaris' commencement speech to The School's graduating class of 1995 left everyone in stitches, many laughing to the point of tears; it wasn't monumental in that "the weight of the world is on you now" way, but uplifting and befitting an alum who made it in that "real world" everyone hopes they'll break into when they leave here.

Graduating from the School in 1987, he went on to teach Writing Workshop part-time before moving to New York City. "I really wanted to write for Soap Operas," he says. He reads regularly on NPR; freelances for many magazines; makes up the modestly titled theater group, "The Talent Family," with his sister, Amy; his first book, "Barrel Fever," went paperback this June; he's working on his second; and he continues to clean people's homes and apartments, a job he's had as long as he has lived in New York, even after he became a celebrity.

Talking with him is like channel surfing. Talking about the woman who owns the house we're in he points out: "None of her plants are real." Because of National Public Radio's Bob Edward's refusal to say "boyfriend" on the air when referring to Sedaris' lover, Sedaris now refers to Edwards as "my cocksucker." In his college years writing for F he created the character Maureen Gridlock based on a self-styled "feminist, Marxist, lesbian" Art History instructor at The School. Mocking her he says, "We must be political. Yeah, it's awful that people are being shot around the world and thrown in ditches.,but ya know, 'One Life to Live' is on in fifteen minutes so why don't we..." Critiquing the opening line of a Writing Workshop student's paper he wrote, "'I suppose it depends really on how one looks at something from the inside, that makes it a big deal or anything.' This is the first sentence in your paper and it makes absolutely no sense at all. This is followed by sentences that make even less sense ... I believe you took bong hits and made phone calls between sentences ... I don't think you are a stupid person. I can get along with stupid people because I feel sorry for them. I think you are a lazy person..." No matter what he's talking about he seems to have the gift of finding the humor in everything, that common denominator that allows us all to laugh at ourselves.

Not everyone appreciates Sedaris' sense of humor. When he read his first story on NPR, "Santaland Diaries," many calls and letters were unenthusiastic to say the least. The story he read based on his true adventures hitchhiking with a quadriplegic to San Francisco didn't go over well either. It wasn't people with disabilities who complained; they found it very supportive. It was suburban white middle-aged women who had no idea what people in those circumstances really felt and decided it wasn't politically correct enough and railed against Sedaris. I can only imagine him laughing at it all, relaxing with a cigarette at the home his boyfriend owns in France, finding it fodder for another story.